IEA (2024), Tracking Clean Energy Innovation Policies, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-innovation-policies, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Scope and design

This G20 Energy Innovation Policy Guide is an open resource that initially covers 94 government interventions whose primary target is to develop technologies (or technology ideas) that hold the potential to accelerate clean energy transitions but whose products still carry technology risk, i.e. their technical performance in the market cannot yet be guaranteed or insured by financial institutions to the same degree as products with a proven record of commercial operation.

Included policies are those that aim to improve the chances that not-yet-commercial technology designs – which offer improved performance or lower costs compared with the existing leading solutions for their applications – will go on to attract widespread investment, shrink any remaining technological performance risk and accelerate progress towards societal goals. Most focus specifically on clean energy for a secure, equitable, net zero emissions future. The policy targets therefore range from basic research project members to SMEs honing new products, large-scale demonstration project developers and even public understanding. While many innovation policies explicitly reward or aim to spur innovation in financing, business models or social enterprise, policies that target these outcomes without a goal of supporting technology development are not within scope.

The guide’s dashboard is not comprehensive but rather aims to showcase the range of innovation policy designs adopted by governments around the world in recent years, and how the features of their implementation vary. Each entry is classified by the type of policy chosen by the government in support of their clean energy innovation goals. These policy types are accompanied by descriptions of how they work and what design options they encompass.

Each entry is included in the broader IEA Policies Database. Clicking on country names and policy types takes the user to filtered views of this database that show the full list of related entries, some of which are not in the guide. Where interventions cover more than one policy type, they appear under only one category in the guide (typically the element that is the most creative or distinctive) and under all related policy types in the underlying database.

Four overarching innovation policy pillars

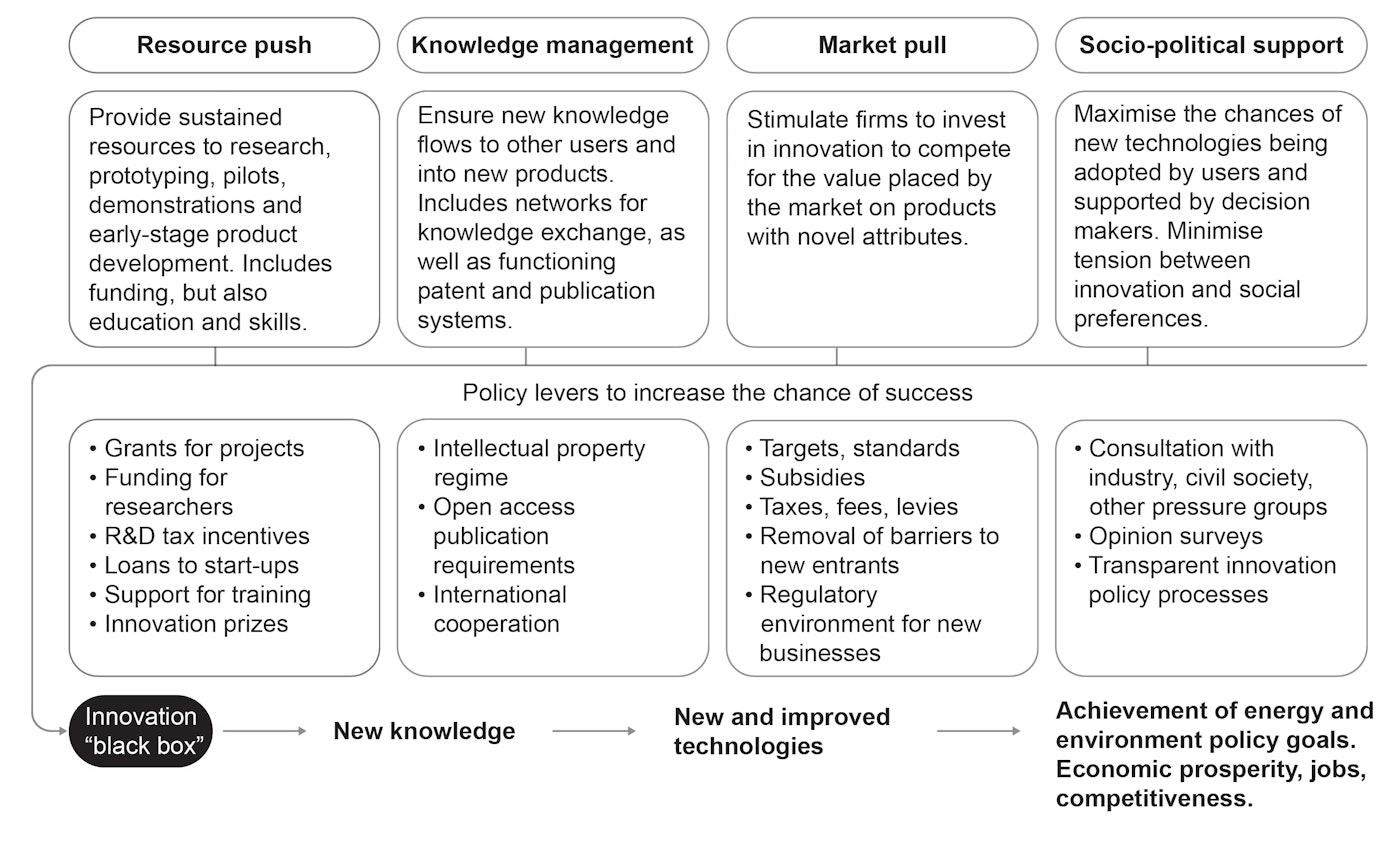

The main functions of clean energy innovation systems can be grouped under four headings. An innovation system will struggle to translate research into technological change without action under each of these headings. These four headings are used to structure the guide’s dashboard.

Resource push: a sustained flow of R&D funding, capital for innovators, a skilled workforce (e.g. researchers and engineers) and research infrastructure (laboratories, research institutes and universities) is required. These resources can come from public or private, including philanthropic, sources and can be directed to specific problems or basic research.

Knowledge management: it must be possible for knowledge to be exchanged easily between researchers, academia, companies, policy makers and international partners.

Market pull: the expected market value of the new product or service must be large enough to make the R&D risks worthwhile, and this is often a function of market rules and incentives established by legislation. If the market incentives are high, then much of the risk of developing a new idea can be borne by the private sector.

Socio-political support: there needs to be broad socio-political support for the new product or service, despite potential opposition from those whose interests might be threatened.

Four policy pillars (functions) of effective energy innovation systems

Open

The challenge of tracking market pull policies for innovation

Experience suggests that market pull policies are highly effective at fostering innovation, but they rarely have technological innovation outcomes as a primary objective, if it is an objective at all. Policies including tax incentives for investment in clean energy projects, public procurement of low-emissions products, standards for environmental performance, carbon pricing, electricity market regulation and bans on polluting technologies all indirectly support innovation. They amplify the incentives for established firms and newcomers to gain a competitive edge through technological change, for example by improving the quality of their product or reducing the price. However, because their primary target is investment in the supply of, or raising the demand for, products that are already technically demonstrated, most policies that spur innovation via “market pull” are not included in the scope of “technologies innovation policies” for the purposes of this dashboard.

The need for a broad-based approach to science, technology and innovation policy that smoothly connects innovation policies to technology diffusion is recognised by the proposed transformational agenda for science, technology and innovation policy.

“Transformative” science, technology and innovation policies

In April 2024, the OECD Committee for Scientific and Technological Policy (CSTP) has published an Agenda for Transformative STI Policies.

STI can make essential contributions to meeting the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, disruptive technologies, and growing inequalities. However, governments may need more ambitious STI policies and apply them with greater urgency if society is to achieve transformative change.

Generating relevant scientific knowledge, technologies and innovations at the pace and scale for transformative change depends on functioning STI systems. Sustained investments and greater directionality in research and innovation activities may be needed, and these should coincide with a reappraisal of STI systems and STI policies to ensure they are “fit-for-purpose” for transformative change agendas.

The Transformative Agenda proposes three goals for STI policy makers:

- Advance sustainability transitions that mitigate and adapt to a legacy of unsustainable development

- Promote inclusive socio-economic renewal that emphasises representation, diversity and equity

- Foster resilience and security against potential risks and uncertainties.

There are multiple pathways for reorienting STI policies and systems to meet these goals, reflecting national conditions. The Transformative Agenda outlines six STI policy orientations to help drive transformative change:

- Direct STI policy to accelerate transformative change

- Embrace values in STI policies that align with achieving the transformative goals

- Accelerate both the emergence and diffusion of innovations for transformative change

- Promote the phase out of technologies and related practices that contribute to global problems

- Implement systemic and co-ordinated STI policy responses to global challenges

- Instil greater agility and experimentation in STI policy.

The Transformative Agenda highlights concrete actions in support of these orientations, organised around 10 policy areas that broadly map onto the policy types outlined in this deliverable. These policy areas include R&D funding, the research and innovation workforce, and international R&D cooperation.

Many of the necessary reforms are familiar to the STI policy community, but barriers remain, for example, in scaling-up and institutionalising innovative policy designs. The OECD is preparing additional guidance to aid policymakers in implementing these policy actions and the Transformative Agenda’s policy orientation

Impact assessment and evaluation

Evaluation of clean energy innovation policies has risen to the top of many governments’ agendas. A key impetus for this renewed interest is the global focus on more ambitious targets for emissions reduction and the recognition that clean energy innovation is critical for reaching the Paris Agreement goals. The urgency means the process of energy innovation needs to be accelerated, without cutting corners on safety or the reliability of the energy system.

Policy evaluation is a critical element for improving citizens’ trust in governments’ decision-making processes, and enabling sound public governance that ensures that public funds allocated to clean energy solutions are used in the most efficient and responsible ways. However, while well-grounded evidence will help governments adopt best practice in innovation policy design to meet decarbonisation targets, scholars have emphasised that knowledge about which support mechanisms most effectively drive clean energy innovations, and under which conditions, is ominously scarce.

The topic has not always received adequate attention among energy policymakers. However, the current level of engagement indicates an opportunity to share experiences and the latest knowledge with the decision-makers that are designing and refreshing clean energy innovation policies. We invite submissions of evaluations and impact assessments to energyinnovation@iea.org.